10 Questions With… Kim Mupangilaï

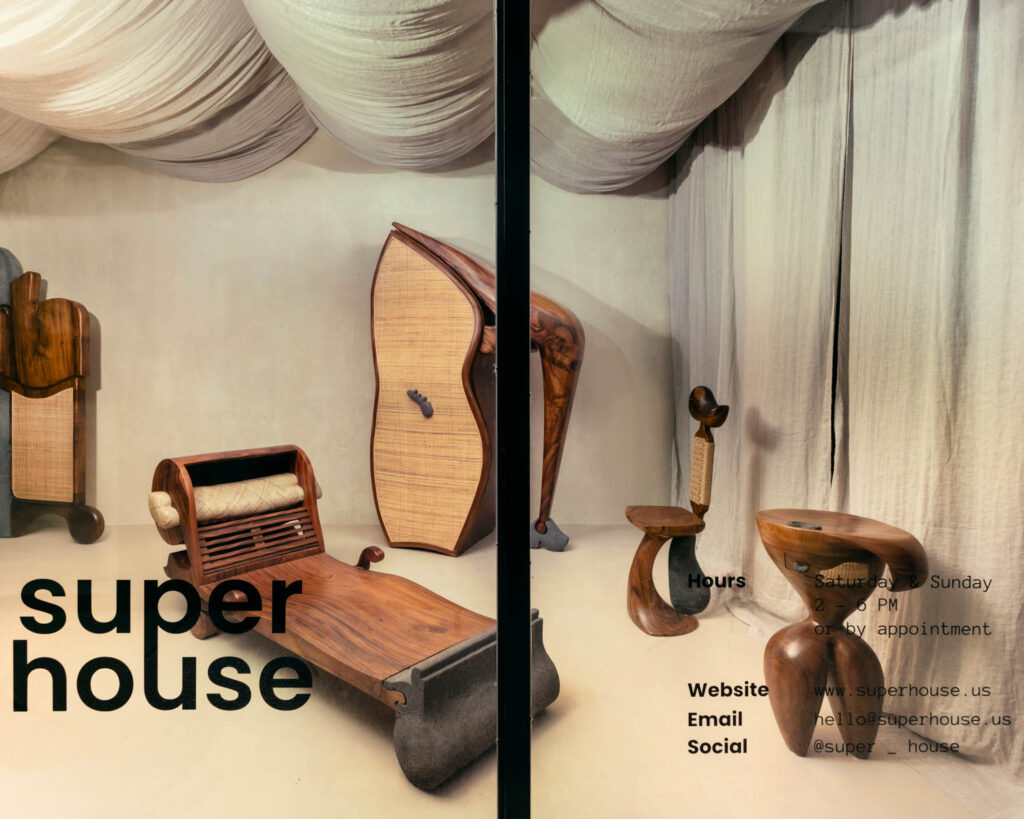

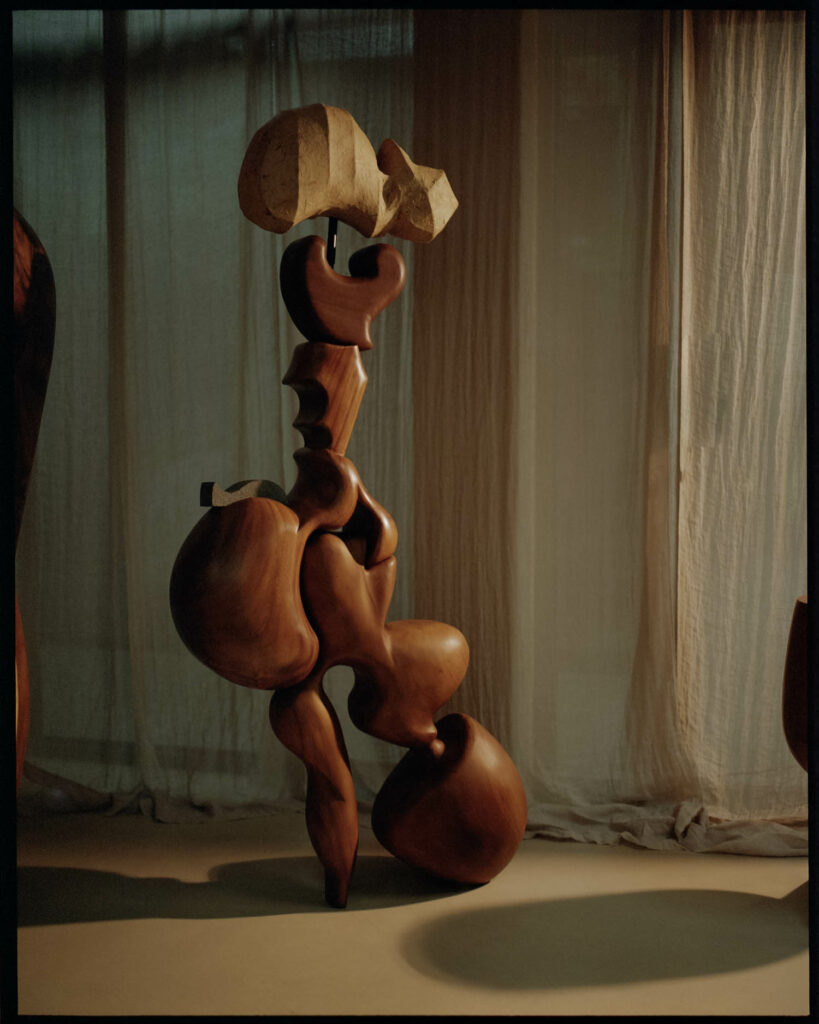

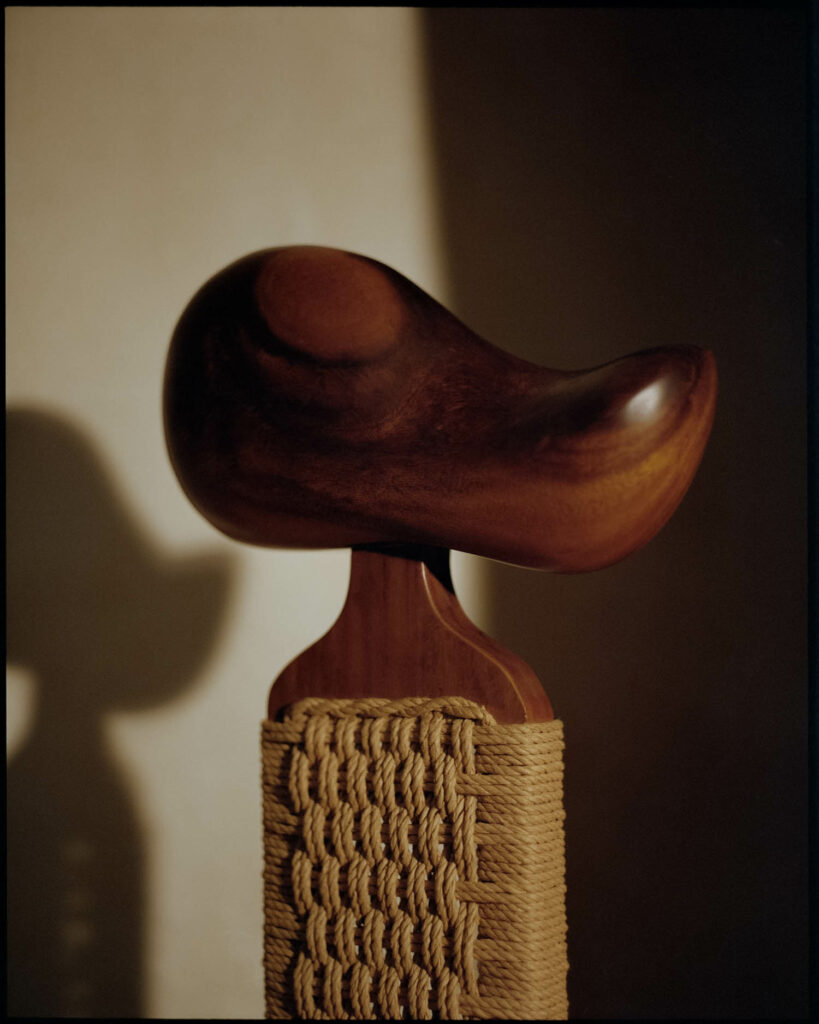

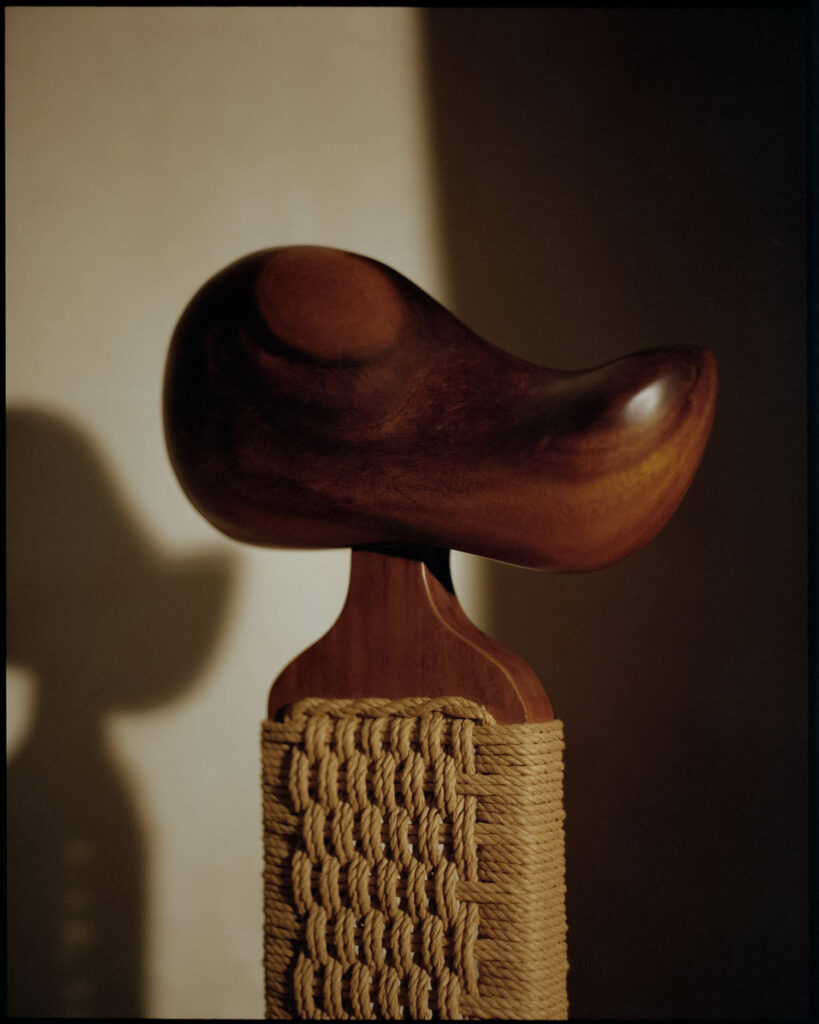

With teak carefully carved to anchor volcanic stone and woven banana fiber, Kim Mupangilaï’s corporal sculptures take on lives of their own. These functional artworks—limber armoires, amorphous tables, and puzzle-piece loungers—stem from the young designer’s personal exploration of cross-cultural identity. Each material is carefully chosen to reflect her Belgian upbringing and, perhaps more potently, offer an introspective quest to better understand her Congolese roots. On view as part of the young talent’s “Hue/ Am/ I – Hue/ I/ Am” solo show at New York gallery Superhouse Vtrine—running through August 19—the Kasaï capsule collection manifests as much from the up-and-comer’s attempt to code-switch and blend seemingly disparate symbolic elements as it does self expression. Both intellectual and creative impulses are successfully assuaged, and to captivating effect.

Impressively, this conceptual and aesthetically-compelling body of work is Mupangilaï’s first foray into furniture. After extensive studies in graphic design and architecture, the talent began her career developing interiors. It was months of backpacking the world that eventually brought her to New York. Moving to the city in 2018 to join her partner and expand her horizons, she began working for an established firm on numerous high-end residential projects and eventually solo-designed her friend’s bar: Greenpoint, Brooklyn’s now beloved Ponyboy. Developing an affinity for and steadfastly accumulating vintage design along the way led her to establish online shop, E N L A M É S Á. Over time, this appreciation for meticulously-crafted objects inspired Mupangilaï’ to begin ideating her own concepts.

All of this coalesced when seasoned culturemaker Stephen Markos—founder and principle of alternative functional art platform Superhouse Vitrine—picked up on Mupangilaï’s talent and asked her to participate in a group show. However, It wasn’t until the 2022 edition of preeminent collectible design fair Design Miami/ that the two began collaborating. One of the designer’s first furniture concepts—an intricately layered room divider—featured as part of Markos’s Curio showcase. This summer’s solo show reveals the full fruits of this initial output.

Mupangilaï spoke to Interior Design about her cultural background, thought process behind her first furniture collection, and design aspirations.

Kim Mupangilaï Talks Design, Cultural Narratives, and More

Interior Design: What first brought you into contact with architecture and design?

Kim Mupangilaï: I grew up in a small Belgian town among cows, farmers, and fields. Once I graduated high school, I was dead set on studying interior architecture, but had to wait because I also had a passion for typography, books, and paper—tangible items from different eras—and so decided to pursue a degree in graphic design first. I’ve alway been drawn to vintage things with emphasis on ‘things;’ objects that have a story to tell. As a little girl, I spent hours rummaging through my grandparent’s attic finding old photos, clothing, vinyl records, and other little knick knacks. It was like a time capsule. These explorations set the tone and ever since, I’ve developed designs with a narrative approach.

ID: How does your Congolese heritage and Belgian upbringing inform your work?

KM: From an early age, I was fascinated by African currency tools, musical instruments, and traditional hairstyles because of the variety of shapes, ornamental detail, and meanings they could represent. Some even had the look and feel of fine artwork. Exposure to this rich cultural offering came from my Congolese grandfather. My Belgian grandfather taught me the basics of woodworking: joinery, turning, and other handicraft techniques. This proved to be an important foundation for design school, where I honed my technical skills even further but also began learning theory.

ID: How do references to Belgian culture come into play?

KM: I never had nor have the intention to design in a certain style because the pieces I create have their own identity. However, over the past few months, multiple people have said that the pieces on view in the exhibition remind them of the Belgian Art Nouveau architecture. Ironically, this movement emerged during the Belgian colonization of the Congo. Because of that, I welcomed this association as it proved that viewers were indirectly deciphering the links to Africa I was intending to convey. Having been able to render materials like teak, stone, rattan, and banana fiber—symbolic of the Democratic Republic of Congo—in sinuous forms that evoke that style helped me drive this point home. While rattan is traditionally found in baskets, rugs, and textiles, banana fiber derives from leaves commonly used for cooking, serving, and preserving food.

ID: How does the cross pollination of different cultures inform your work?

KM: I think it’s imperative to be mindful of the cultural landscapes when designing or creating. This approach acts as the main differentiator from myself and what’s expected from other designers. I believe one cannot be inspired by certain communities, indigenous cultures, and their art without acknowledging the basic principle of extraction. It’s important to give back and credit those who might not benefit from your purpose within design.

The cross pollination of different cultures has piqued my young peers’ interest. I’ve had several students reach out to me for interviews and perspectives on culture, cultural appropriation, and so called vernacularity within architecture and design. Recently, I was asked to teach about similar topics at Parsons School of Design. These inquiries confirmed my suspicions that there’s, unfortunately, a lack of information out there on this matter. I strongly believe that there are much larger conversations to be had. This has fueled my aspiration even more to teach and be more vocal about these issues. The educational side of design has been a career path that has always intrigued me aside from the practice itself.

ID: What was the impetus for expressing this conceptual framework through furniture design?

KM: Growing up in a cross-cultural household yet western world, it became my natural instinct to blend in with my surroundings. This resulted in never fully understanding nor finding my identity. My Belgian roots and Congolese heritage became the yin-yang of a conceptual process. This helped me shape my work into a montage of opposites, translated into a perfect amalgamation of my deep appreciation for African artifacts and western design.

Furniture is my tool of choice when it comes to artistic self expression. I’m able to share and shape my unique narrative with the intention of offering a feeling of community, new perspective, and insight with the hope to encourage fresh discourse and conversation. I often believe that so much more can be ‘said’ through art than articulated in words.

ID: How does the Kasaï collection demonstrate this thinking?

KM: For me, this furniture series has opened Pandora’s Box. Even though I discovered a lot about my heritage through deep dives into historical and ancestral stories, it left me even more curious and driven to delve deeper. It all started with research into Congolese art history. I was particularly intrigued by the concept of currency tools, items that were used to trade land or animals but that also symbolized major events in one’s life. Inspired by the interchanging of these significant meanings and uses, I started to develop my own formal alphabet. Music and rhythm are such a big part of Congolese culture, I wanted to make sure this was articulated in the works well by playing with volume, contour, and scale. The sketches of these abstract shapes became more refined over time and began to emerge in the designs I was creating.

ID: What do each of the standalone pieces represent?

KM: Someone recently pointed out that my work reads as ‘macro and micro,’ meaning that each piece simultaneously works by itself and as part of a whole. Aside from that, they felt that the work indirectly indicated how we, as a people, conceive of our identities and present them to the world. We’re all made up of so many different parts that only become visible upon closer inspection or introspection. It’s those interpretations that intrigue me the most. From the very beginning of the process, my goal for the work was to provide the viewer with the space to look inward and reflect on their own heritage, upbringing, and cultural landscape.

ID: What draws you to the more artistically-inclined collective design industry?

KM: While there is no shortage of ‘personal’ explorations in the collective design industry, these works go beyond that approach and more deeply into the territory of self reflectivity, the ultimate contemplation of trying to merge two different cultures. The specific and personal narrative that embodies the work reflects a certain exclusivity—not in the luxury sense—but in that each piece is unique and unreplicable. Each piece is artistic in its own way, combining complex design with practicality even though they might appear to be that way. This playful duality reiterates the concept of ‘art/design is subjective’ and can be interpreted however the viewer sees fit.

ID: What’s next for you? What would be your dream project?

KM: I’m still in the exploratory phase of my career as an autonomous designer, but I am excited to continue pursuing new opportunities and evolve. I am currently working on new pieces that will hopefully come out at the beginning of 2024. Eventually, I’d love to be commissioned by a museum to develop a piece that sheds light on the concepts of cultural landscapes and appropriation. Another dream of mine would be to develop a work for a fashion house I admire. And of course, as mentioned before, I’d love to teach.

Kim Mupangilaï Crafts Furnishings that Reflect Her Heritage

read more

DesignWire

10 Questions With… Superhouse Founder Stephen Markos

Interior Design caught up with Superhouse founder Stephen Markos, who is creating a platform to present queer design.

DesignWire

‘Ingrained’ Exhibition Explores Works in Wood By Women and Non-Binary Artists

Ingrained, a show of work by six women and non-binary artists and designers, opened at Superhouse’s petite Vitrine gallery in NYC.

DesignWire

Behind Alda Ly Architecture’s New Furniture Design Venture

Alda Ly and her minority-owned, majority-women firm bring their effervescent, human-centric vision to furniture showroom design for the first time.

recent stories

DesignWire

10 Must-See Best of Year Award-Winning Projects

Submissions are open for Interior Design‘s Best of Year Awards—the design industry’s premiere design awards program. Submit by September 6, 2023, or sooner!

DesignWire

Zanele Muholi’s Sculptures Shed Light on Human Rights Issues

Zanele Muholi’s new sculpture exhibition on display at Southern Guild in Cape Town offers a response to South Africa’s femicide and LGBTQ+ stigmatization.

DesignWire

An Exhibit Unravels the Significance of Wool in Oslo, Norway

An exhibition in Norway aims to make visitors aware of the history, ecology, and global dynamics of the extraction and production of wool.